Propaganda is a term which is commonly understood to be a tool used by dictators to bend the people to their will. It is more efficient that using violence, and can get similar outcomes of compliance from an unsuspecting populace.

Jacques Ellul, in the 1960s, wrote an insightful book on the topic. Behind the plain cover, he unpacks the art of the propagandist, the strengths and weaknesses of propaganda and where is it used today.

Surprisingly, he doesn’t just look at the communist totalitarian states like the Soviets and Mao’s China, but also the Western democracies too.

He explains the difference between hard and soft propaganda, the psychological truths which are employed and the dangers too. For example, using the propaganda of hatred is the most effective form, but can easily get out of hand if the people are not given the outcome they have been propagandised to desire. While propaganda of hope is slow to influence, it produces far better long term outcomes.

One key element in the book is the interplay between the technological society and propaganda. As the society becomes more technically sophisticated, propaganda becomes more influential and more necessary to maintain the systems. In fact, Ellul predicts that at some point in the future, everyone who engages with the system will be influenced by propaganda. There is no escape.

Looking at our culture today, if we use the Internet, listen to the radio or watch TV, then we are being propagandised. The only way to resist this is to never use them. I have a friend who only gets her news from her clients. I would say she is the least propagandised person I know. She never discusses the ‘current thing’, and only talks about her local life with family and friends. She doesn’t use social media and rarely uses the Internet.

Propaganda can’t force a society, a community or a person to act against the general trend, but over time it can influence the values and beliefs of a culture. If it is used to physically coerce a populace, it must be accompanied by government power. We saw this with the state propaganda during the lockdowns. Government agencies delivered messages which were alongside police action. Consequently, these were very effective.

There are antidotes to propaganda. Firstly, we can just ignore it. We can remain sceptical of it and rather than simply accept what we hear, ask the question ‘Why are you telling me this?’ Though by disengaging from it, we are cutting ourselves off from meaningful involvement in modern society.

Another way to defend ourselves against propaganda is to constantly measure the messages against an older more established narrative like Common-Sense, wise sayings and proverbs or even sacred religious texts. Propagandist find it difficult to manipulate these engrained ideas. But again, we have the same problem. If we only engage with these ancient ways, we fail to properly interact with the culture.

We may think we can completely escape the effects of propaganda, but as Elllul points out, we can’t when we live in a highly centralised technological society. If too many people opt out of the official propaganda, then the system begins to collapse. Without a central narrative, cracks widen in the technological society. We are starting to see this today, as people are using other sources of information. These share news stories from a view point which is contrasting to the official media. Resulting in polarisation of opinion in the culture.

So, if a complex technical society needs propaganda to function, and we enjoy our hot showers, the benefits of the Internet and streaming services, then we have to embrace propaganda. The question which is left begging then is, which propaganda should we allow to influence us. Which propaganda to we choose?

All effective propaganda has an element of truth to it. The idea of the Big Lie, which becomes more and more believable every time the propagandist tells it, isn’t actually true. There has to be an element of truth in it to make it believable.

So the best ‘propaganda’ to engage with is not only the one which tells a version of the truth, but the most accurate version possible. This is the message we need to engage with. If we align ourselves to the truth in a situation, we are more likely to have better outcomes than if we hold to a partial truth or even a lie.

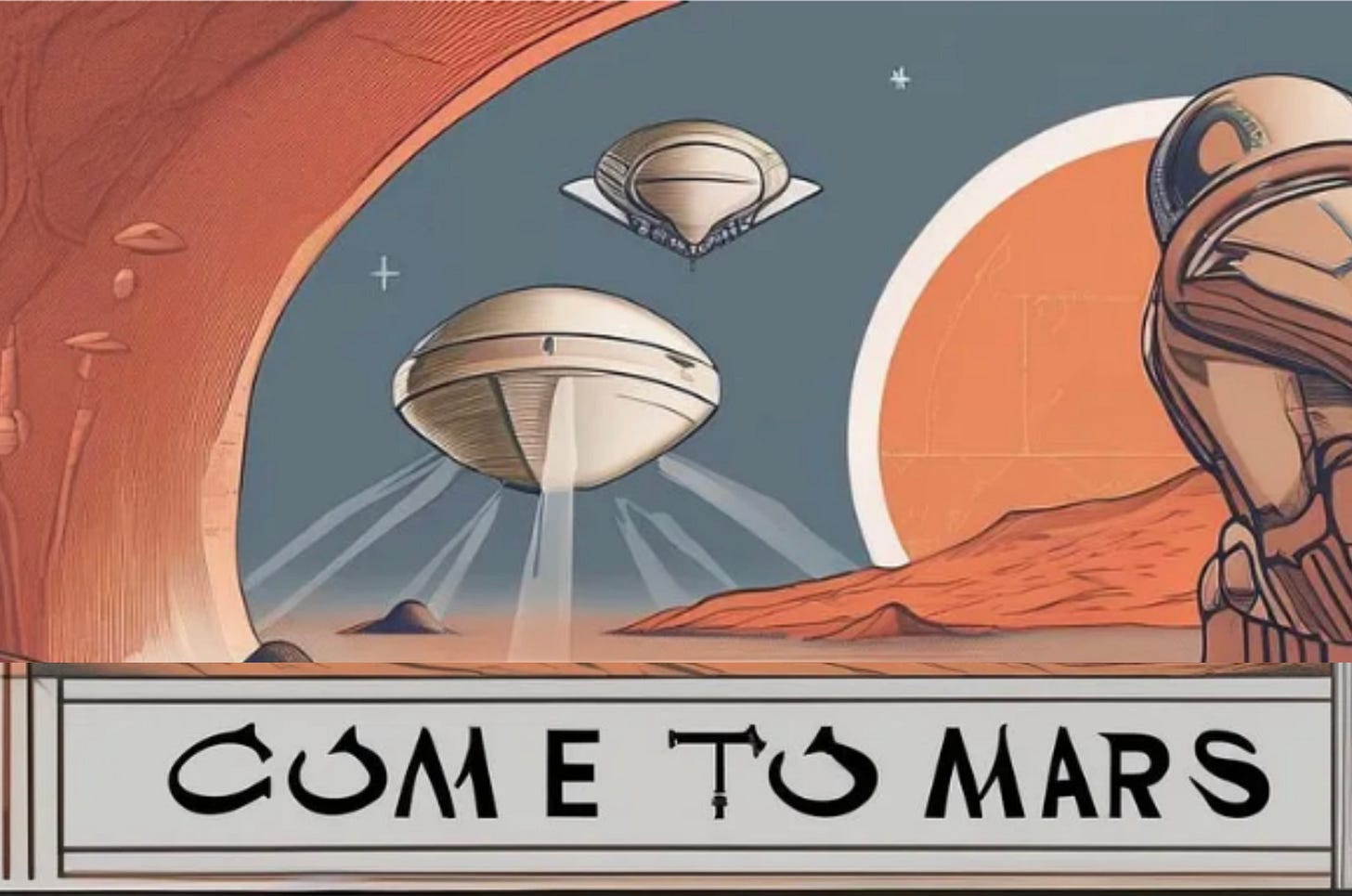

AngloFuturism recognises the need for propaganda in a functioning modern technological future, but it needs to be a truthful narrative. Lying leads us to make missteps, mistakes and ultimately reaches dead ends. While truthful speech leads us to a secure future amongst the stars.

‘Truthful propaganda’ might seem an unsettling term, but if Ellul is correct in his assessment, then propaganda is an unavoidable element of a modern technological society.

Are you saying that propaganda is comparative to the meta-narrative of a society?